Hannah Sward, Strip

As a man, I’ve had an uneasy relationship to strip clubs. As an underage drinker, sneaking into the Karlyn Lounge on the outskirts of my small Pennsylvania town, I was titillated by the spectacle of local girls baring their all to a soundtrack of pounding, Top 40s rock. And as I aged into my twenties, strip joints, though not a frequent destination, continued to, well, arouse.

By my thirties, however, something had changed. One of my fellows in a recovery program asked me accompany him to a strip club on Albuquerque’s East Mesa (which, apropos of not much, is a pediment, not a mesa). The guy had, he informed me, tried to eat the business end of his .38 the night before, but the bullet had proven a dud. Click, but no KAPOW. And now he wanted to watch naked women.* The idea, probably, was that having me along would discourage him from drinking. In truth, I’d have accompanied him anywhere that evening, just to see he made it home unperforated.

But seated at our indifferently wiped table, I felt uncomfortable, an effect that intensified when a barely clad blond oozed our way and commenced to gyrate to the dance music that poured from the club’s PA system, her groin inches from my face. My problem was not one of prudishness—I was not offended. Rather, I couldn’t bear to go full lizard brain in front of this undulating stranger, though full lizard brain was the state she sought to produce. More, I could not relinquish that sort of control in view of my friend, the wait staff and the other dancers, not to mention the crowd of sad sacks who’d paid their cover in order to sit at those grimy tables and participate in what is surely the most inadequate substitute for intimacy that exists on this spinning rock.

And speaking of those sad sacks, I couldn’t bear the possibility that I might be mistaken for one of them.

So I looked away, which made things worse. It turns out that the only thing more embarrassing than lasciviously ogling a near-naked woman in front of a bunch of strangers is pointedly not to ogle her. I snuck a surreptitious glance at my watch—how long, I wondered, before we could leave?

I’ve rarely felt so alienated as I felt sitting there, saddened for this hard-working young woman in this joyless circumstance, for her confederates, for the unhappy-appearing men for whom this was the best the night had to offer. Strip clubs, with their farcical pantomime of actual human connection, their bottomless, unrequited neediness, turn out to be some of the saddest places on earth.

Nothing in memoirist Hannah Sward’s Strip discourages me from this view. Abandoned by an, erh, free-spirited mother to be raised by her father, the poet Robert Sward, the young Hannah transacts her childhood in an atmosphere of not-exactly-benign neglect, a seeming afterthought to Sward pere’s quest for spiritual enlightenment, geographic restlessness, and succession of female partners—temporary and variously willing “moms.” More than once, this laissez-faire approach to parenting delivers the child Hannah into the clutches of sexual predators. Summers are spent in the bohemian world of her mother, whose need for male companionship authors another form of neglect. Yet it’s in her mother’s Florida home that Sward forges her life’s most consistent relationship—that with her half sister, the somewhat ostentatiously named Rilke.

There’s a common view among progressive Westerners (among whom I count myself) that a parent’s primary task is to help his or her children to “find themselves.” That’s good as far as it goes. On the other hand, that paradigm for parenting has been the go-to for self-absorbed parents from Australopithecus onward. In Sward’s case, it lands her as a young adult in a strange city without marketable skills or the ability to soldier through an eight-hour workday. With rent due and an empty larder, an escort gig provides the most obvious remedy. Predictably, stints as an exotic dancer and lap-dance dispenser, as well as more prostitution, and drug and alcohol addiction—all the grim appurtenances of the commercial sex trade—follow.

As a dancer, as a stripper, Sward has the looks but, unlike half-sister Rilke, doesn’t have the moves. And there is the relentless pressure to stay thin—a task made easier by a line of crystal meth. And then another. And another. Until those lines stretch to infinity.

Through all of this, though, Sward writes. And her parents do, at last and with varying degrees of intent, come through—her mother financing her return to college, her father bequeathing her a powerful love of language. Ultimately, and in fits and starts, Sward does find herself. One only wishes that her path had been an easier one, although that easier path would have resulted in a less gripping memoir.

Hannah Sward’s Strip is fearless, unstintingly honest, and rendered in English that’s less lyrical than conversational—language employed by real people divulging real, and oft painful, things.

So should Strip be on your reading list? Oh, hell yes.

Strip lands on the shelves on September 6. Preorder it at your local bookseller or at bookshop.org, an online retailer that donates a portion of its profit to independent bookstores. (No one, but no one, loves the written word as much as the men and women behind the counter at your neighborhood bookshop. Let’s keep that in mind when we pop for our next book. Jeff Bezos has more than enough of your money.)

* Over the years, I’ve come to doubt the truthfulness of this tale. Bullets are pretty reliable. Like as not, he just wanted company while he ogled the wares at the local titty bar.

Ellen Meister, Take My Husband

Confronted by an image of black dots surrounding an elliptical splotch, most human eyes will perceive said splotch as expanding, as if one were rushing headlong toward the mouth of a tunnel. Though disconcerting, the effect is an example of the eye tricking itself — a run-of-the-mill optical illusion.

Expanding hole illusion

Though the quantity of light impinging on the viewer’s eyeballs remains constant, measurements show that his or her pupils nonetheless dilate. Neuroscience tells us that the brain operates with an infinitesimal delay with respect to changes in its physical environment, an effect of the time required for information registered by the eye to reach the brain and for the brain to decide what the hell to do with it. Thus, there’s a lag between the world as we perceive it and the world that actually exists.

To compensate, researchers believe that our minds constantly make guesses about the immediate future — I’m seeing what happened a few microseconds ago, but I’m projecting toward the physical present. And so, the pupils. The brain models the splotch as a dark place we may soon enter. Accordingly, it directs the pupils to widen, to admit the greatest possible amount of light.

Even at this most immediate level, then, we project ourselves into the future.

We are, by constitution, future-directed creatures (a fact that makes me a little impatient with “live in the present” types who’d have it that times coming constitute unworthy grounds for consideration). Were we built to live primarily in the present, we’d likely not have persisted as a species. We are too weak, too vulnerable to master all challenges as they come. Thus, evolution has wired us to project into the future on scales ranging from the microsecond to the decade. We cannot help it, and with respect to our ability to avoid danger or death, that’s a good thing.

And it illuminates a troubling component of human existence. Faced with the death or disablement of one we love or upon whom we depend, most of us jump quickly to the terrible event’s aftermath. C’mon, admit it. Will I be okay, we ask ourselves. Will I have enough resources? Will my circumstances change? Will another appear to take the departed’s place? Will I be able to provide for my children? Will I, myself, continue?

These thoughts are awful, shameful, and wildly out of line with the actuality of the situation. At a moment that is profoundly not about ourselves, we nonetheless become our own focus. This is a terrible, yet irremediable feature of being a future-oriented organism, programmed by natural selection to forecast times coming to best enhance our own prospects for survival. But because we are social creatures, evolutionarily endowed as well with capacities for love and loyalty, we are appalled by such thoughts and we quickly quash them.

Though perhaps not always?

Author Ellen Meister’s Laurel Applebaum works the floor at a Long Island Trader Joe’s, a job that’s at once tiring and a welcome respite from husband Doug’s overwhelming neediness. Her sales clerk’s paycheck, however, is no match for the couple’s expenses and each week witnesses their savings dwindle. Doug, a failed shopkeeper, refuses to find work, wiling away his hours watching TV and adding to his already unhealthy girth. He is, in short, a heart attack waiting to happen, and his reluctance to shoulder responsibility extends to the most trivial household chores. Hard-working Laurel, by contrast, spends her days crushed by financial anxieties, an increasingly passionless marriage, and catering to Doug’s endless whims.

When she gets word that Doug’s been rushed to the hospital following a car crash of unknown severity, she’s assailed by those terrible, all-too-human imaginings — what if Doug lay breathing his indolent last on an emergency room gurney? What if she’s to arrive at the ER to discover Doug dead? In Laurel’s case, these thoughts are tough to push away. Really, Doug’s demise would solve so many things! There is, in truth, a fat insurance policy, not to mention respite from Doug’s numberless demands. Doug, however, has weathered his encounter with the Grim Reaper with scant injury. He awaits her in an ER carrel, little damaged but needier than ever.

By degrees, and with the aid of the grandfatherly Charlie, a Trader Joe’s coworker, Laurel slips from imagining Doug’s death to actively promoting it. After thirty years of penny-pinching and servitude, does she not deserve the ease and freedom a Doug-free life would bring?

And is Take My Husband, then, a dark tale of wickedness and foul intrigue? Certainly not! Meister’s ability to render the grimmest situation hilarious seems coded into her very DNA. I confess to being a literary chatterbox — why else would I engage in this oft thankless pursuit? — and I invariably bend my spouse’s pretty ear with running commentary on each book I review. (I’m lucky to have a patient spouse, although I’m not sure I want her to read Take My Husband...) But even at such a remove, Meister’s latest side-splitter had my darling L-ing, as the kidz all say, OL.

Will Laurel regain her moral compass before she embarks on a new career as a killer? Are Charlie’s efforts as disinterested as Laurel believes? Will new flames ignite to replace the extinguished old? Just how hard will Doug prove to kill? Take My Husband, rendered in Meister’s trademark breezy prose, is a literary paradox — a hilarious exposition of the grim places to which the human heart might travel.

Meister’s latest will land at a bookseller near you on August 30. Preorder (really, do!) at your local bookstore (better) or at bookshop.org, an online retailer that donates part of its proceeds to independent booksellers.

Novels of the Missing — Jessica Chiarella’s The Lost Girls and Rebecca Copeland’s The Kimono Tattoo

New Mexico, thirty years ago. My kids and I have just finished dinner at our favorite Chinese place, located along Albuquerque’s busy Route 66. I’m at the register, settling the bill, when I look around to check on my son and daughter, something I’ve probably done more than once in the last minute or two. My son, aged eight, is there, daydreaming about something or other, mostly likely a dogfight involving supersonic fighter jets. He’s where he’s supposed to be.

My three-year-old? Absent. Missing. Vanished. Kapoof. Quite likely taken, I immediately fear. I tell my son to wait with the cashier then run back into the restaurant. It’s a big place, with several cavernous dining rooms. First, I check the table we’ve just vacated but find no sign of her. I dash into each of the dining rooms in turn, charging deep into them. “Jean? Jean!” I call at the top of my lungs, hoping she’s somewhere among the tables, too short to be seen. All diners pause to stare, chopsticks frozen en route to their lips.

Probably every parent has experienced this terror at some point — you’re in a crowded market, a festival, a concert or rally or gathering of the tribes. You’re a decent parent, at least you try to be, and you would trade whatever breath you’ve got coming to tack one extra breath onto the life of your kid. So you check on her reflexively, knowing, as you do, the dangers of crowds. And, each time, she’s in easy reach. Until she isn’t. Physiologically, the response is instantaneous — your heart hammers, sweat sprouts from your palms, your breathing races and turns shallow. On the emotional end, that black, indeterminate thing boiling in the center of your chest can only be called dread. It’s there all the time, just waiting to be activated. When you find her (and almost always, you will), the effects persist: exhausted, you feel, with a tiredness that goes to the marrow, and nauseous, your belly charred by adrenalin and bile.

In my case, I grabbed my son’s hand and dashed into the parking lot, hoping to blockade any escaping kidnap-mobile with my own dad body if necessary, yet crushed already by the certainty that whoever abducted her would be long-gone, my delay in searching the restaurant a fatal mistake. Then I see her, standing tiny and alone by the rear bumper of my sedan, happy and proud to have negotiated this transit alone. She’s three-feet tall, the parking lot is dark, a driver backing out a pickup or SUV would never have seen her. I reach her, she beams at me, and I do something I’ve not done before and will not do again. I turn her around, lean down, and swat her bottom with considerable intent. Her face crumples, not so much from pain, I suspect, but from sheer surprise. I am not a hitting old man.

But I want her to remember this moment, I want this lesson to stick. Or maybe I’m just so adrenaline-poisoned that I can’t think straight. Maybe I’m simply out of control.

The particular terror associated with the loss — as opposed to the death — of a loved one has dominated the news-cycle of late, with the nation transfixed by the disappearance of van-life influencer Gabby Petito. We, as a species, seem addicted to narratives, real or otherwise, of loved ones who’ve slipped, or been sucked, into the ether. It’s a trope of story-telling from crime fiction (Lisa Jewell’s excellent Then She Was Gone and Tana French’s In the Woods) to the literary (for example, Frederick Busch’s Girls). Indeed, a search of Goodreads turns up 2049 titles for “novels about missing persons” while the search string “fiction about death” returns about one tenth of that number. As readers, as humans, we seem more compelled by people’s disappearance than we are by their actual extinction.

Why should this be so? Rationally, one might expect the reverse to be true — disappearance offers some hope, however slim, that one’s loved one may some day reappear. Whereas death is so non-negotiably final, the afterlife so profoundly open to question.

The inexplicable vanishment of those we cherish allows, indeed demands, our imaginations to run wild. We envision unspeakable sexual assault, starvation and squalid captivity, our loved ones chained in dark, airless rooms, caked with their own feces, rash-bedeviled by their own urine. We are tortured for them. Better, surely, to know, irrespective of the anguish the knowledge might bring. An overdose, a suicide, murder in whatever form — at least, we’d be assured they’re not being slowly dismembered or consumed morsel by agonizing morsel by some neighborhood cannibal. Stephen King argues that the monster’s unveiling will always be to some degree a disappointment…and a relief. In Danse Macabre, he tells us, "Nothing is so frightening as what's behind the closed door. The audience holds its breath along with the protagonist as she/he (more often she) approaches that door. The protagonist throws it open, and there is a ten-foot-tall bug. The audience screams, but this particular scream has an oddly relieved sound to it. 'A bug ten feet tall is pretty horrible', the audience thinks, 'but I can deal with a ten-foot-tall bug. I was afraid it might be a hundred feet tall’.”

The annihilation of a loved one is the ten-foot bug. Their disappearance? The ambiguous horror of the closed door.

But why are we drawn to that closed door?

Recent efforts in the area of biocultural literary analysis suggest that the human penchant for story — for narrative — is hardwired into our very gray matter: no mere happenstance, but an adaptation that conduced to our success as a species (Boyd, 2010). One such adaptive function may be reflected in the stories we spontaneously construct and tell ourselves — namely, our daydreams (for a fuller discussion, see Gottschall, 2013). Commonly, in those diurnal musings, we counterpose to ourselves some obstacle — the boorish interlocutor, the unjust accuser, the inapproachability of the beautiful other — and ninety-nine times out of a hundred, we overcome! The boor is chastened, the lovely one wooed, the accuser him- or herself condemned! Walter Mitty envisions his heroic existence in each of us.

But daydreams of this type may serve something more than a slightly embarrassing itch for self-aggrandizement. They may, in fact, function as practice, preparation for the challenges our social order presents us. We will, if we’re lucky to live long enough, encounter numerous rude vulgarians, weather multiple unjust indictments, become infatuated with someone who seems out of reach. Our conflict-ridden daydreams school us for these moments so that we come to them not as babes but with a quotient of experience, speculative though that experience might be.

The narratives we construct for those we love have a different flavor. To such degree as my daydreams feature my son or daughters, the lives they posit are success-filled, disease- and disappointment-free, sun-drenched, well-loved, and with no ominous cloud furring the horizon. I doubt I’m alone in this. It’s one thing for me to imagine myself beating the odds. For my loved ones I desire the odds be stacked in their favor; for them, my dreams are dreams of lives fulfilled — healthy, happy, and rich in meaning.

Yet what am I — what are we — to do with the small, yet non-zero chance of their vanishment? It does happen. How can we mentally rehearse the disappearance of those we adore, prepare ourselves for the categorically unacceptable? This must to some degree underlie our fascination with stories (fictional or otherwise) of loved ones gone missing. Stories of lost loved one allow us to practice such loss at a safer distance, to experience this particular horror at a level several times removed. (1)

In the plight of Gabby Petito, the onlooker finds opportunity for such practice. For those who are normally made, simple human empathy — also an artifact of our evolutionary development — sounds within us an echo, however attenuated, of the misery the Petitos must certainly feel, gifting us a scintilla of familiarity that might conceivably help us navigate this particular region of Hell, should we find ourselves consigned there.

Fiction does this one better. In the case of the Petitos, Gabby and those who loved her, we have only empathy to guide us. We can imagine their pain, yet we lack access to the gooey viscera, that interior space where the searing heartache abides. In Then She Was Gone’s Ellie and Laurel Mack, for example, we’re granted access to these interior spaces — we witness Ellie’s rage, worry, and terror, her slow diminishment and final acceptance; we participate with Laurel in the circumscribed, chronically wounded existence of a parent whose child has gone missing.

(It’s also likely, the psychology of loss notwithstanding, that tales of vanished loved ones simply lend themselves more readily to the novel- or scriptwriter’s pen. For the missing, their narrative importantly continues. For the known deceased, their final breath constitutes a period to their narrative’s last sentence. Those who mourn them continue in another narrative altogether.)

The pain of siblings gone missing — survivors’ pain — undergirds both novels I review in today’s post.

The Lost Girls by Jessica Chiarella

Protagonist and part-time Goth bartender Marti Reese’s days are haunted throughout by her sister’s 1998 disappearance. When a Jane Doe turns up on the coroner’s bench twenty years later, the deceased bears similarities to the missing girl and Marti is called in to assist with identification. Though the remains are not her sister’s, the event provides the nucleus of what becomes an award-winning podcast, conferring upon Marti a mild celebrity. A possible tie between a late-nineties murder in Marti’s childhood neighborhood and sister Maggie’s disappearance draws Marti and producer Andrea into an extra-legal investigation and provides grist for their podcast’s season two. Their efforts snare Marti in a sinuous scheme that ultimately puts her life in danger.

The pizazz of Chiarella’s writing, the superimposed pluck and instinct for self-destruction that characterize her heroine, put one in mind of Ellen Meister’s amateur sleuth and constitutional wild child, Dana Barry (see posts for The Rooftop Party and Love Sold Separately). But Chiarella serves up Marti Reese minus Meister’s subversive humor. What does come though in The Lost Girls and what I most admire about the book is its pervasive sense of anger. This, I think, is the sensibility most apropos, indeed essential, to a novel of female vanishment in this world where violence against women is routine and in many cases institutional. More, as a cis, hetero male, Chiarella makes me appreciate in a way I have not before the disquieting ambiguity of women’s attraction to male partners. (Petito’s autopsy results, not available at the start of this writing, make this point quite brutally as well.) Men — we are attractive, we are desired, and we are sometimes extremely dangerous.

The Kimono Tattoo by Rebecca Copeland

Child disappearance furnishes the emotional underpinnings to Rebecca Copeland’s debut outing, The Kimono Tattoo. Copeland’s heroine, Ruth Bennett, plies her trade as a translator in Kyoto, the Japanese city where she was raised by missionary parents and where her younger brother Matthew disappeared decades earlier under mysterious circumstances. When she receives an offer to translate a new novel by a revered Japanese author, long presumed dead, she cannot resist.

In short order, the events of the manuscript and a pair of real-life murders disturbingly conflate. Ruth finds herself caught in a dark design involving traditional kimono-making, Japanese tattoo, dog fighting, human trafficking, and even, perhaps, her missing brother. At the center of all of this is an ancient scrap of fabric with a troubled history and complex provenance. As Ruth struggles to unravel the threads that ensnare her — and, possibly, find her sibling — she’s aided by her boss and her boss’ (handsome, of course) son, a pair of plucky Japanese tattoo punks, a renowned fabric dyer, a traditional dance instructor, and more. One gets the sense either that the Japanese are the world’s most accommodating people or that Ruth possesses some special ability to entice people to put themselves at risk. They are an entertaining bunch, however!

One detects in The Kimono Tattoo — with its cadre of amateur sleuths, its circumspect violence, and its evocation of a mostly kind universe a hefty hint of the spirit that animates the cozy mystery. With respect to this pair of novels, it is the gentler of the two.

To my particular sensibility, The Lost Girls and The Kimono Tattoo suffer from the unreality of The Big Revealment in which dark and baroque schemes are shown to drive each novel’s events. To my eye, the crime story is better served by acute characterization than it is by complex plotting. But, hey, that’s just me. In neither book is this an actual deficit. For one must keep top of mind the first of Updike’s rules for successful reviewing — don’t fault the author for not achieving an effect she didn’t intend. And, truth told, most readers delight in the uncovering of a hidden design. They’ll be entertained by this duo of crime novels in a way they’d not be by, say, Busch’s Girls.

Each of these books is competently written, each in a breezy, quick-moving style, but does either serve the purpose that biocultural literary analysis might posit for it? Does either prepare us or provide emotional training for loss that outrages our sense of the universe — the arbitrary, lacerating subtraction of a loved one from one’s existence? I would argue yes, as much as any tale can do. Chiarella’s and Copeland’s heroines are scoured by their respective losses in the way any of us would be scoured, as I’d have been scoured had I not found my three-year-old on that terrifying New Mexico eve. They are harmed, as any of us would be harmed, in a way that will scab but never seal. Yet each mucks through in her own more-or-less damaged way, as any of us would muck through. Each proves willing to open herself to fresh pain on the slim prospect that her missing loved one might be redeemed.

But on the ultimate question of healing, a question more acutely interrogated in Chiarella’s The Lost Girls, would any of us — should any of us — desire to heal? I would argue not. The pain of a loved one’s disappearance, of the uncertainty of their fate, is the indelible mark their vanishment leaves on the life of anyone unfortunate enough to experience it. We might accommodate such pain but we will never be well. And that is as it ought to be. Such pain should be embraced and held onto — it is the claim that one gone missing holds on us. It is something we owe.

Buy The Kimono Killer and The Lost Girls at your local bookshop (preferred) or at bookshop.org, an online retailer that donates part of its profit to benefit local booksellers. Seriously, do any of need to finance Jeff Bezos’ space-cowboy fantasies?

(1) For this notion, thanks to my most insightful interlocutor, the smokin’ hot theologian Myriam Renaud.

Works cited:

Boyd, Brian, On the Origin of Stories (Boston, Harvard University Press, 2010).

Busch, Frederick, Girls (New York, Harvard University Press, 2006).

French, Tana, In the Woods (New York, Penguin Books, 2007).

Gotschall, Jonathan, The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human (New York, First Mariner Books, 2013).

Jewell, Lisa, Then She Was Gone (New York, Atria Paperback, 2018).

King, Stephen, Danse Macabre (Pocket Books; Reprint Edition, 2011).

Martha Cooley, Buy Me Love

Or, running in place in turn-of-the-millennium Brooklyn.

Martha Cooley’s Buy Me Love explores the ways in which we humans get stuck and the partial and contingent means by which we free ourselves (if free ourselves we do).

Ellen Portinari is a free-lance editor with an empty billfold, a checking account barely worth the name, and retirement savings best described as dismal. In her fifties, she’s a poet with a solitary, long-ago chapbook and a singleton among her married friends. Crippled by the death of his lover in a terrorist bombing, brother Win is a composer who no longer notates, consuming vodka with kamikaze abandon and rendering his compositions in the form of uninterpretable squiggles. Father Walter, a famed baritone, mourns the accidental loss of his own, single musical composition, unable to take up anew his composer’s pen. Ellen’s unexpected love-interest, Roy Lince, squeezes his living from a collection of part-time teaching gigs, while Ennio, his adopted son, cannot move beyond the death of his birth father. Blair Talpa, a young, trans street artist, traverses her Brooklyn landscape largely unseen, crippled by the disappearance of her one, real human contact, her Asperger’s-afflicted brother.

If life with its devilish array of trick pitches often authors the terms of our entrapment, it is nonetheless true that we devise many of those terms ourselves. Our day-to-day may be unsatisfying, yet welcome, if ambiguously so. When Ellen wins an eye-popping sum in the New York Lottery, the solution to many of her problems...and Roy’s...and Win’s...would appear to be at hand, yet her chief concern is the caboodle’s-worth of changes that a mammoth influx of cash will inevitably produce. Free from worries about money, will she know who she is? Or will the windfall open space for other changes, smaller in magnitude if no less significant?

I am not immune to the pleasures of lyrical, even precious language (lookin’ your way, Cormac M.), yet it seems that the language I laud most in these pages is that which does the praise-worthy job of getting out of the way, conveying its tale in journeyman style, its beauty in its simple transparency. Such is Cooley’s accomplishment in Buy Me Love. If I were to levy a single, minor criticism, it would touch on dialogue attributed to eight-year-old Ennio. His precocity notwithstanding, much that he says rings too adult to my ear. Of particular value here is Cooley’s attention to the exigencies of dating and sex during menopause. This is a subject that merits attention from writers of fiction and, in Buy Me Love, Cooley portrays it in a way that’s both sensitive and pleasingly matter-of-fact.

Purchase this fine novel at your local bookshop (best) or at bookshop.org, an online retailer that donates part of its revenue to local booksellers (still pretty good). There’s a particular saintliness to these folks, our neighbors and friends, who bend their lives to make sure that ours are filled with the written word. Let’s keep them thriving!

Writing the Novella, Sharon Oard Warner

A couple of weeks back, a reader of this not-so-august column dm’d me with these kind words — “I like the way you don't just review plot or craft but suggest ways to read.” Suggesting ways to read a book is one thing I try to do, and I want to do it right now and right here. So lissin up, novella (and, really any other type of fiction) writers — read Sharon Oard Warner’s Writing the Novella with highlighter in hand. This is craft writing at its best.

Warner’s style is casual and humorous, her voice generous and, at points, vulnerable as she recounts her own particular struggles to perfect her craft. And she is a champion of this somewhat ambiguous beast, the novella, positioned as it is between the brevity of the short story and the expansive breadth of the novel. Though Writing the Novella is aimed at, well, novella writers, Warner’s writing and journaling assignments (she is a former professor — see note) will deepen any fiction writer’s grasp of her characters and point the way as she teases out the whats, and more importantly, the whys of her tale. Warner grounds her advice, always on point, by drawing on three “touchstone” classics — Ethan Frome, The House on Mango Street, and Fahrenheit 451 — even as she mines the novella oeuvre more broadly.

Warner’s scholarship with respect to this subject matter is gobsmacking — she must have read every craft book ever written, and her Recommended Reading list would keep any industrious reader beavering away for a year. Writing the Novella would serve well as the primary text for a graduate course focusing on this particular form but any writer, at any stage of her career, will find plenty here to enrich her work. The novella, Warner suggests, may be coming into its own in this, our current, attention-deprived milieu, so perhaps this is the moment to wipe down your computer screen, make yourself a cup of coffee, and start banging those keys. If you are inspired to tackle this shorter form, make sure that Warner’s Writing the Novella sits close at hand. Trust me, you’re like to get lost, and this marvelous piece of craft writing will point your way home.

Buy Writing the Novella at your neighborhood bookseller or at bookshop.org, an online retailer that uses part of its proceeds to benefit local bookstores. Books are an intimate thing, best acquired face to face from someone who loves them as much as you do. Let’s keep those local shrines to the word on a page alive and kicking.

Note: I said I was done with the practice of reviewing work by people I know, yet here I am, back at it. Sharon Warner was one of my first writing professors at the University of New Mexico, where I participated in writing workshops while plodding soullessly on a Ph.D. in an unrelated field. I’ve always esteemed her, which is why I agreed to engage this particular volume, my previous resolutions to the contrary. Fortunately, Writing the Novella is terrific. Otherwise, I’d not have reviewed it.

Alix Ohlin, We Want What We Want

We contain within ourselves pockets of injury. Our lives — once imagined as incandescent with promise — turn mundane. Lovers remembered become different people altogether, and those stories with which we comfort ourselves prove untrue. We avert our eyes from these places of hurt — to peer into them feels too scouring, too at odds with our daily struggle. Or we cover them over with lies we craft for ourselves, deceits tailored to shield us from our disabling realities.

Alix Ohlin, in We Want What We Want, is a spelunker who shines her torch into these hidden spots, revealing with an explorer’s pen those truths her characters might wish to remain concealed. Ohlin’s characters take up the weight of child-rearing, work, marriage, yet remain tied to the hope and possibility of their youths. Drifting apart of one-time friends and lovers weakens those ties yet renders them more piquant. Newcomers enter her protagonist’s lives, shattering fictions that make their days bearable. For others, loss and gain go hand-in-hand — security embraced paired with passion forgone. Relationships that appear unimportant come to a close, leaving those who people We Want What We Want alienated and unrooted. Amanda, in The Brooks Brothers Guru, believes herself averse to community only to learn how urgently she desires it — even as it’s unclear whether community can embrace her. In The Detectives, secrets uncovered leave Amber’s own life not necessarily worse, but more complicated. For the narrator of Service Intelligence, injury sparks rage that’s both unquenchable and paralyzing. Filled with human melancholy though they might be, Ohlin’s tales do offer their quotient of grace. Within their pages, new loves are discovered, weary loves are accommodated, a widower finds himself awash with love for love itself.

In We Want What We Want, Ohlin never succumbs to the temptation of style over story and her dialogue crackles with urgency and verisimilitude. She is a lover of the first-person, employing the intimacy it offers to participate with (in particular) her female characters as she brings them up against their defining truths. Any one of these thirteen tales would find a comfortable home in any quality anthology. Indeed, I expect to see some of them in that format. As you can probably tell, I’m pretty wowed.

We Want What We Want comes out on July 27. Buy it. And read it. But do so, if possible, at your local bookseller or at bookshop.org, an online retailer that uses part of its revenue to benefit local bookstores. Let’s work to keep those temples to love of literature thriving.

Brett Riley, Lord of Order

Given the popularity of religious dystopia like Hulu’s adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Amazon Prime’s of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, one might wonder whether this particular sub-subgenre flirts with oversaturation. To any such doubter I would point to Brett Riley’s stunning Lord of Order as evidence that this particular vessel is far from overfull. Really, there is always room for another great tale.

As Lord of Order, Gabriel Troy protects and oversees the principality of New Orleans under the authority of the Bright Crusade, a globe-encircling Protestant fiefdom born in the long-ago past of a genocidal cleansing of the world’s unbelievers, memorialized among the faithful as the “Purge.” When Troy captures a leader of the dissident Troublers, he’s made uneasy by her claim of a new Purge in the offing — even as they speak, she tells him, the Crusade is driving suspected heretics in the thousands toward his city, there to be imprisoned, or subjected to something worse still. The arrival of an emissary from Supreme Crusader Matthew Rook confirms the Troubler’s assertion. Troy and his deputies understand this measure will damage irreparably their city and the many citizens they’re sworn to protect. By degrees, they struggle to abandon the obedience they have always practiced, to resist even the demands of their faith.

Riley’s New Orleanians are vivid and well-drawn, each torn by the agony induced by acting out of accord with lifelong belief, by making room for a dose of Troubler spirit in their own quaking souls. (An exception to this is McClure, a deadly teenage orphan and expert tracker whose closest companion is an enormous Rottweiler. An unbeliever, McClure suffers no scruple in ignoring the Supreme Crusader’s mad edict.) It’s in Riley’s examination of the difficulty in knowing the will of the dematerialized Hebrew deity with Whom Allah and God share DNA, that Lord of Order transcends the adventure novel to become literature. He — God — is, above all, silent. One can never truly know His will.

This struggle to know falls most harshly upon Deputy Lord Gordon Boudreaux, whose indecision and reluctance to resist dooms him the role of Rook’s torturer and collaborator, a role that burns his soul to ash.

“The skeleton strapped to the torture table knew nothing…that had been clear as soon as they had dragged him in by his wrists and thrown him on the table like a cut of meat. Yet there lay the man’s teeth, and here were the pliers, in Boudreaux’s hand…now, after so many trips to this blight of a room, he could believe anything about anyone, especially himself…The things he had done had poisoned his dreams, his faith. No love or charity here. No Godliness, unless God’s insane. If this is justice, it’s sick and perverted. So are my friends, who passed me this cup. None of them so sick as me…God had been silent, and for the first time in his life, Gordon Boudreaux could not accept the mystery…Everyone was vile. Everything was senseless.”

The physicist Steven Weinberg has averred that “With or without religion, good people can behave well and bad people can do evil; but for good people to do evil — that takes religion (https://rtraba.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/adesigneruniverse-weinberg.pdf).” An honest rendering of history would reveal a situation that’s considerably more complex (consider Stalin’s USSR, the Khmer Rouge, the French Terror, and the subtlety of evil in each of us), yet Weinberg’s words contain an element of truth. In Boudreaux’s case, the edicts of his Supreme Crusader scour his soul hollow.

Interestingly, though the Roman Church persists in Lord of Order only as a battered remnant, the Protestant Crusade has adopted many of its trappings. The Crusade bows to a leader of popish infallibility. Lords of Order and their Deputies submit to vows of chastity. The condemned are subject to torture in the hope they may recant their sins and find a place in Heaven, echoing the logic of the Roman Church’s autos-da-fé. These, Riley may hint, are measures a religious movement that seeks to hold the world in its authoritarian grip must embrace.

Lord of Order achieves its denouement in a lengthy battle scene of Homerian scope and Cormac McCarthyan specificity. For some readers, these scenes might prove difficult. I would argue, however, that war is, above all, horror, and as horror it ought to be portrayed.

This is a novel that could not be more timely, given the political climate we currently endure. The attraction of right-wing conspiratorial thinking by conservative evangelicals (https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-qanon-has-attracted-so-many-white-evangelicals/) and the partial religious underpinnings of the January 6th invasion of the United States Capitol ( https://divinity.uchicago.edu/sightings/articles/biblical-attack-capitol?fbclid=IwAR04QgsD0hSP_7M3st1WM3Ctodg3TPPJxhqFy7EhP0wmEk3GmbISPZIae-E) underscore the authoritarian longings that grip many evangelical hearts.

Perhaps our recognition of this, however inchoate, accounts for the resonance engendered by Atwood, Pullman, and now, conspicuously, Brett Riley. They are prophets of the terrible could-be. I was blown away by this book, and I want you to read it. Buy it at your local bookseller (best) or at bookshop.org (still pretty good). But buy it. Do.

Susan Mihalic, Dark Horses

Lolita bites back in Dark Horses, a freshman effort by novelist Susan Mihalic.

There are depths of experience so profoundly plumbed by our literary forebears that no writer who hopes to sound them can avoid comparison. Writing a battle scene? Homer and Tolstoy are the giants you must fight. Penning a private eye? Hammett, Chandler, and MacDonald (to name a few) stand between you and your place in the canon of crime. And, as in the present case, if you take on the sexual exploitation of young women, it’s Nabokov with whom you’ll contend. None of these literary ghosts wish you ill. But they do demand you show yourself worthy. They’ll make room for you, if it’s room you deserve.

In Mihalic’s Dark Horses, high-school junior Roan Montgomery is an up-and-coming competitive rider, a darling of the equestrian set, a secret drinker, and her coach and Olympic gold medalist Monty Montgomery’s lover. The relationship would be problematic enough if the elder Montgomery were not her father. Yet he is, and Roan’s abuse at his hands extends deep into her childhood. Mihalic’s tale is one of an athlete at the highest level, managing the rigors of her sport even as she juggles schoolwork, the tempestuousness of an alcoholic, emotionally unavailable mother, and her own yearning for adolescent romance. All of this, as she struggles with her own sense of complicity in Monty’s depredations and fights to regain control of her sexual being. As her resistance mounts, so does Monty’s determination to control her contacts, her affections, her very movements. And, of course, her body. Ultimately, it will require an act both desperate and extreme to free her of her father’s priapic talons. This is an escape story, and it is a heroic one.

Mihalic’s deep knowledge of the equestrian universe informs this tale at every turn. One feels the jumps, the grass-scouring landings, the precision of dressage. One smells the deep aroma of sweating horses, knows their angers and affections and fear. Honestly, I don’t particularly like horses, but Mihalic’s novel made me wish to be among them.

But can Dark Horses nudge Lolita aside enough that Mihalic might stand at Nabokov’s side on this particular podium? I would answer with a resounding yes. Like Nabokov’s, Mihalic’s is a first-person narrative, forgoing the ironic misanthropy of Monsieur Humbert for the dauntlessness of a young woman who recognizes her oppression but refuses to be defined by it, who insists at any cost upon becoming free. Both Nabokov and Mihalic understand that the intrusion of sexuality into a parent-child relationship destroys any prospect of actual intimacy. Though monstrously jealous, neither Montgomery pere nor Humbert-squared know the hearts of these girl children for whom they are charged to care. In the opposite direction, the knowing is deeper, or at least grows so — Roan and Lolita are survivors, and a survivor must know her abuser’s whim.

More, in reading Lolita decades after my first perusal, I find myself fatigued by Humbert’s compulsive, fussy wordplay (not to mention the obnoxious improbability of preteen Lolita’s initiating their first sexual congress). Roan’s is the lucid voice of a young woman coming to know her worth, understanding she has only herself upon whom to rely, and determining that — no matter the cost — the hand that guides her destiny will be her own.

So buy this book. Seriously. Do it now. You’ll find Dark Horses at your local bookseller (better) or at bookshop.org (almost as good). Mihalic’s is a fresh vision and hers will be an important one. Saddle up, boots in the stirrups, and start the ride.

Ellen Meister, The Rooftop Party

Amateur sleuth Dana Barry is back in Ellen Meister’s The Rooftop Party, applying her photographic memory and surprising detective chops to another mysterious killing. The catch being that, this time, she’s not sure the murderer isn’t herself.

There can be a strangeness to the role of serial good guys in crime fiction, arguably the genre in which recurring characters most commonly appear. I’ve thought a lot about this of late, as I’ve chipped my way through an omnibus edition of G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown stories (see note). Father Brown is now and again summoned by police to crime scenes by dint of his well-known sleuthing skills. As frequently, though, he manages to be on the scene as a as a matter of simple happenstance. One feels blessed in this case that life does not mimic art. In decades upon this earth, the closest I’ve come to an actual murder is to have worked with the wife of a guy whose brother killed a hitchhiker. If real murders were as common as one might infer from the Father Brown stories (or those featuring plenty of other amateur detectives), we’d live our days knee-deep in the corpses of the unjustly killed. Indeed, we’d be damn lucky to reach advanced age ourselves.

But such unreality serves a literary end. To engage such tales, a reader must bow to their improbable premise. And in so bowing, the reader cedes control. I’m to be taken on a ride, one acknowledges, and I grant the writer permission — simply by agreeing to read the first word of the first page — to commandeer the wheel.

And so it is with Manhattan’s Shopping Channel — Dana’s employer and seemingly a dangerous place to be. In The Rooftop Party, The Shopping Channel finds itself under pressure from the internet and its plethora of opportunities for effortless online shopping. To right this possibly sinking ship, the Board has brought in a new CEO — the outwardly pious, habitual sexual harasser Ivan Dennison — from the electronics industry. Dennison intends to reorient the company from fashion sales to electronics, and everyone at headquarters understands that layoffs are on the way. When Dennison takes an involuntary (and unobserved) dive from the rooftop at the Channel’s yearly Christmas party, the question is motive — was the new boss murdered on account of his sexual predations or for reasons economic?

Dana’s problem is this — she knows Dennison aggressively hit on her, yet she has no idea what she did about it. He’d slipped, you see, a dose of Rohypnol (the date-rape drug) into her martini and the time of his killing is a blur. Learning what she’d done in that moment — did she push him? did she not? — is key to her relationship with hunky cop boyfriend, Ari Marks, and perhaps to the survival of The Shopping Channel, itself.

Meister’s amusing gallery of characters — Dana’s tone-deaf father and shopaholic sister; Meghan, her best friend/manager; Lorenzo, Shopping Channel sound guy and Dana’s once lover; Sherri, her congenitally sour boss; Ari, the police detective with male-model looks — are back with all the rest. Southern belle, Ashlee, Dana’s new assistant, is a particularly droll addition.

Meister’s prose is streamlined and transparent, reflecting that high level of craft that eschews calling attention to itself in favor of serving its tale. And at moments, reading The Rooftop Party, I would find myself grinning with the sheer, headlong fun of it. Dana’s phenomenal memory and eye for detail seem less central to The Rooftop Party’ than they were to Love Sold Separately, this novel’s predecessor (see my review of September 14, 2020 on pauleberly.com), and I might observe that this latest murder’s solution flirts with being exogenous to its book’s broader plot. The Rooftop Party is, however, a stay-up-all-night-worthy addition to the Dana Barry saga, and I can only hope Meister won’t make us wait overlong for her next installment.

Do read The Rooftop Party! Pre-order online (bookshop.org), and do it now before you forget. (The internet — it’s quite effortless!) Or — better — order it at your local bookstore. The world is soon to reopen — let’s get out and engage our booksellers in the flesh.

Note: Beloved by such pillars of crime fiction as Julian Symons and P.D. James (Symons would have it that Chesterton’s shorts are rich to the point that one should sample only a few at a time, while James would aver that their sheer deliciousness should prompt one to read with gluttonous abandon), Chesterton’s tales are nonetheless marred by their racism, antisemitism, and Catholic triumphalism. I am not one who’d argue that historical authors should be deleted from the canon for their failure to conform to modern understandings of sexuality, religious tolerance, or race. And I am not suggesting that readers ought to avoid Chesterton for his failures in this regard, disagreeable as they might be. Rather, I suggest that Chesterton ought to be shunned for simple lack of literary merit. I’ve now read nearly all of his Father Brown corpus and I can report that barely a tale stands out to the point that I much remember it. If you want a Father Brown fix, watch the BBC series with its mostly defanged and ecumenical cleric. Skip the actual stories — I’ve read them so that you don’t need to.

Suzanne Koven, Letter to a Young Female Physician

The clinic is cool and dimly lit. I lie on a none-too-comfortable gurney, enrobed in the standard, unmanning hospital gown. Around me, machines whir and click; air enters through the hospital’s HVAC system, a white-noise whoosh. The resident, when he steps through the door, is gowned as if for surgery — he sports a tunic of lifeless green, his hair shrouded by something like a giant, paper brioche.

I must confess something here — I’ve made over the last couple of years a hobby of, well, “educating” residents (and, really, medical personnel in general). When you’re quite possibly dying, you need something to keep you distracted and amused. Upon this particular guy, I deploy my standard line for these moments when medical sorts snake their fat, rubber tubes down my throat and snorkel about my midsection. This comment, though, is not aimed to provoke — rather, it’s born of my own terror.

In the three years since I started treatment for esophageal cancer, I tell him, I’ve married a woman so precious I’m surprised she gave me the time of day, much less tied her life to a life as contingent as my own. I’ve just walked away from a Ph.D. program and started to write. I’ve got part custody of two little kids. “So you can’t find cancer,” I finish. “Anything else, abandoned tires or rusty fish hooks, all well and good, but don’t you dare find a tumor — I mean it.”

This guy’s training, rigorous as it no doubt was, did not prepare him for this. His body language goes full panic-mode and beads of sweat pop out on his forehead. “Well, you know,” he stammers, “I…I can’t tell promise that. I mean, there…there…there’s no way we can know…I mean about the cancer…until we get in there and — “

At this instant, Dr. Weiss slips into the room. We’ve been together, this man and I, since the beginning of this unwelcome journey. He was, in fact, the doc who first diagnosed this thing that possesses so much potential to kill me. “I just ordered your resident not to find cancer,” I say. “I might’ve freaked him out…”

Weiss uncorks a self-assured grin, positions himself at the top of the gurney, ready with a syringe of knock-out juice and his endoscopy tube. “Don’t worry,” he says. “We won’t.”

I turn back to the resident. “When someone tells you what I told you,” I tell him, “that’s how you answer.” He remains silent as Weiss places his thumb on the plunger that will catapult me to lala land. He smiles his sweet, humorous smile. “Goodnight,” is the last thing I hear.

That was twenty-six years ago, so Weiss’ prediction turned out to be correct. But it could’ve been otherwise. In 1995, esophageal cancer killed 95% of its sufferers within five years of treatment. Quite possibly, it does still. So by any rational measure, the resident had the right of it. Obviously, there was no way he could assure me that my cancer, so boisterously lethal, hadn’t come back. He acted, in that instant, like a proper medical professional, a perfectly appropriate clinician.

But Weiss, with those rash words, “We won’t,” was something more in that moment, something greater, yet less guarded — a doctor. Sometimes, to be a physician, a great physician, one has to go, in the words of doctor/writer Suzanne Koven, “off the charts.”

Koven’s writing of Letter to a Young Female Physician was sparked by an exercise given to newly hatched interns, which invited them to write letters to their future selves. Turning that logic on its head, and nearing the close of her career, Koven wondered what she might say to her younger self as a new fledged doc.

In this series of essays, she touches on death, medical education, personal insecurities, the early AIDS epidemic, groundless belief in physician invulnerability, misogyny and racism in the medical profession, the impact of financial constraints upon the practice of medicine, the frailty and death of aging parents, difficult (me) or noncompliant patients, struggles with food, her own development as a writer, and, finally, the everyday heroism of medical personnel simply coming to work in the face of Covid-19.

Laced through all of this is Koven’s learning to recognize her particular strengths, her journey from insecure intern to the doctor she’d ultimately become — from the twitchy propriety of my gastroenterological resident to the comforting, if somewhat buccaneering, assurance of Dr. Weiss. Letter to a Young Female Physician is the story of her learning, in short, to go off the charts.

“When I first went into practice,” Koven writes, “I had rather firm notions of the proper boundaries between doctors and patients…An older colleague found my rigidity amusing…’You’ll loosen up in time,’ he told me…I think I feared that as a young female physician I wouldn’t be taken seriously unless I maintained an austere facade.”

This task of “loosening up,” however, is confounded by a malady she considers particularly acute in women.

“I believe women’s fear of fraudulence is similar to men’s, but with an added feature: not only do we tend to perseverate over our inadequacies, we also often denigrate our strengths.”

Still, over the years, Koven learns to embrace her less obviously medical strengths, learning at last to adopt an expansive notion of doctoring, one in which technical prowess works in tandem with one’s role as a human being.

“As my colleague Jim predicted, I found my initially rigid standards nearly impossible to meet over time. After all, a doctor is not simply a repository of information but a human being with a personality, a sense of humor, and a point of view.”

And,

“…I always feel like I do my best work when I play the boundary, when I bring myself to the patient as a person. When I go off the charts a little…when I talk with my patients about issues not strictly medical, I feel most like a doctor.”

Letter to a Young Female Physician is a work of near staggering vulnerability. Koven walks readers through her fears of personal inadequacy, her uneasy relationship with the nuts and bolts of chemistry and biology, her early acceptance of inequity in the medical system, her professional fallibility, her struggle to be both daughter and medical advisor to failing parents. We watch her bring her humanity into her medical practice and become a greater physician for it. At points, her militant honesty leads her to suspect herself of worse motives than she likely possessed.

To care for the ill, to really care for them, one must come to them as more than a body of knowledge, a set of technical skills. “I’m not sure that even holistic medicine fully acknowledges the difficult-to-measure therapeutic effects of empathy, attentiveness, humor, intuitive reasoning, the ability to inspire hope, and other qualities sometimes called ‘soft skills’ (or more appreciatively ‘the art of medicine’) and which are as useful in my practice as antibiotics and MRIs, if not more so,” Koven tells us. “Similarly, when I’ve been a patient myself, or when someone I love has fallen ill, I’ve been struck by the importance of these qualities to healing.”

Me too, pretty clearly — sometimes, “the art of medicine” means telling a frightened guy with his bottom hanging out of a hospital gown that you won’t find a tumor that may in fact be there, taking that risk, “inspiring hope,” bringing to bear all of one’s technical prowess yet keeping one tyvek-covered foot firmly off the charts.

Buy this remarkable set of essays from your local bookseller or from bookshop.org, an online retailer that contributes part of its profit to independent bookstores. Local bookshops are the temples in which many of us learned our love of books — let’s keep these places of worship alive.

Suzanne Simonetti, The Sound of Wings

Four women, young and old, negotiate life’s ups and downs in a seaside resort in The Sound of Wings by Suzanne Simonetti.

Sculptor and shop-owner Goldie Knight contends with waning faculties and crumbling finances even as she’s assailed by the scotch-breathing ghost of her long-dead husband. Neither a rich, adoring mate nor palatial oceanside digs can salve hometown girl Krystal Axelrod’s sense of inferiority, born as it is of high-school awkwardness and childhood poverty. Unflappable-seeming Jocelyn Anderson has a handsome husband, a handsome home, and a contract for her second book, but none of these outweigh her fear of losing custody of her six-year-old son and her crushing case of writer’s block. Finally, Daisy Anderson — long dead before the story’s timeframe, but present through her adolescent diary — struggles with disapproving parents and an evasive lover as she contends with new motherhood. These lives become intertwined — friendships form, acrimonies fade, and Goldie, Krystal, and Jocelyn slay personal demons — as The Sound of Wings wends toward the dark, unexpected secret at its core. In this, her freshman effort, Simonetti excavates an important but oft-overlooked truth — namely, that pain, well, hurts, irrespective of the circumstances under which we suffer it. Goldie, Krystal, and Jocelyn enjoy lives of comparative privilege, but privilege doesn’t lessen the misery their problems inflict. Their resolutions, when they come, are not uniformly happy ones, but it’s in this that the story finds its truth and aspires to the level of literature.

Simonetti’s writing is facile but short of lyrical. Yet approachability, not lyricism, is what she’s working to achieve. The story’s animating secret may feel a bit unearned. Still, Simonetti’s promise as a writer is evident and one looks forward to her future outings.

You can buy The Sound of Wings at your local bookstore or at bookshop.org, an online retailer that donates part of its profit to independent booksellers. The joy of capitalism is that one can reward those one favors and punish the entitled. Let’s inflict a little pain on Amazon and look out for the little guys.

Richard Toews, The Confession

Richard Toews examines questions of theodicy, culpability, and loss of story in this novel of Mennonites in Ukraine during the years encompassing the Russian Revolution and Hitler’s invasion of Stalin’s USSR.

Nieder Halbstadt in the years before the Revolution is, in Toews’ telling, a prosperous village centered around farming and religious observance. It is also prey to those sins of the heart that taint all human communities. In particular, the Mennonites of Nieder Halbstadt are superior and self-satisfied, regarding Russian peasants as bestial and Jews as untrustworthy and inferior. Indeed, Mennonite contempt extends even to their poorer co-religionists, so-called “landless Mennonites.” As the Bolsheviks extend their hold across Ukraine, some young Mennonites abandon their passivist tradition, taking up arms in the cause of self-defense. The reprisals for this are barbaric. Famine authored by Stalin’s collectivization of agriculture along with Bolshevik persecution of Mennonite communities causes many to abandon their faith, embracing communism and collaborating against their erstwhile fellows. When Germany invades in June, 1941, Mennonites immiserated by the Soviet lash hail the invaders as liberators, lionizing Hitler as a God-given savior. Some among these become participants in the Shoah. Toews seems to suggest their turning from Mennonite mores is partly traceable to their years of persecution; as one is torn from one’s founding myth, one becomes vulnerable to exogenous evil. Yet, as Toews shows us, the seeds of evil in Nieder Halbstadt were long present.

Toews’ notion that Stalin’s malign reign explains in some part the Nazification of Ukrainian Mennonites is undermined by enthusiasm for Hitler shown by Mennonites in Germany proper. Further, research shows this same argument was made in bad faith by collaborators themselves after the war (see note). Still, the inadequacy of its argument aside, The Confession performs a service by bringing Mennonite actions during the Holocaust back into the conversation.

Buy The Confession at your local bookseller or online at bookshop.org, an internet-based retailer that uses part of its profit to support independent bookstores.

Note: See Ben Goossen, https://anabaptisthistorians.org/tag/mennonites-and-national-socialism/

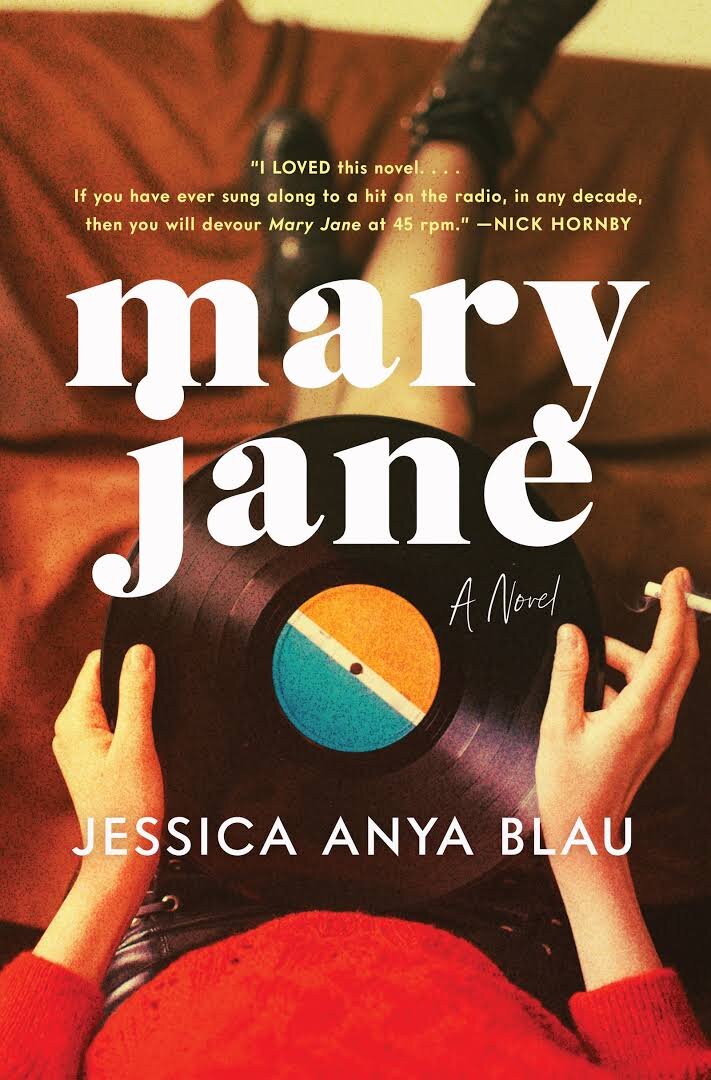

Mary Jane, Jessica Anya Blau

The coming-of-age story continues to deliver in this tender tale by Jessica Anya Blau.

Mary Jane Dillard, a fresh teenager at thirteen, scores a summer nanny’s gig in her upscale Baltimore neighborhood. Her clients? The Cone family, who are Jewish (emphasis on the “ish”) and thus a rarity in 1970s Roland Park. Mary Jane’s own family is of a type that many who were raised in that era will recall: country-club WASPs — upper middle-class, domestically perfectionist, solidly church-going, and skeptical of human unlikeness, particularly as embodied in Baltimore’s Blacks and Jews. The Cones, by contrast, are bohemian, their home a disaster zone, with books, bottles, and dishware scattered on every surface and a refrigerator full of moldering, unidentifiable foodstuff. But the Cone home is one of unfettered spontaneity and overt affection, a contrast to the sterility of Mary Jane’s own homelife. Her charge, five-year-old Izzy, is smart, adventuresome, and loving. Mary Jane falls for the little girl and falls hard. Into this come Jimmy and Sheba, celebrities who move in with the Cones so that Dr. Cone, a psychologist, can treat Jimmy’s addiction. Unpredictability ensues, creating a volatile mix in which Mary Jane loves and feels loved, seen in a way she does not experience at home. The Dillards and Cones are antipodes between which Mary Jane must navigate even as she navigates her own sexual awakening, bringing order (and dependable nutrition…) to the Cone household while concealing its excesses from her parents. Ultimately, and within herself, she must find a way to reconcile the two.

Blau’s writing is breezy, propulsive, and inventive, and Baltimore in the 1970s, as rendered by her pen, is vividly imagined. But it is her big-hearted portrayal of a young girl managing the complexities of the adult world she must inhabit that captivates. The verdict? Read this one. Do.

Buy Mary Jane (out May 11) at your independent bookseller or from bookshop.org, an online retailer that donates part of its profit to independent booksellers. Let’s keep those local temples to love of literature alive and kicking!

The Last Sailor, Sarah Anne Johnson

Allow me to begin with a (possibly familiar…) disclaimer. Sarah Anne Johnson and I attended the same MFA program. I’ve known her since the turn of the century, though our contact has been spare and confined to social media. Even so, I’ve always liked her and esteemed her abilities as a writer. So can you trust this review? I can only say this — if I didn’t like The Last Sailor, I wouldn’t review it (see note).

My reading year began and, now, ends on the early 19th Century North Atlantic coastline, opening with Michael Crummey’s The Innocents and closing with Sarah Anne Johnson’s The Last Sailor. Both tell of the hard life purchased by those who wrest their living from an unforgiving sea.

The Last Sailor’s Nathaniel Boyd, eldest son of Yarmouth Port’s wealthiest landowner, lives alone in a shack he’s erected at the edge of town, solitude a salve for the drowning death of his youngest brother, a tragedy for which he holds himself responsible. His saving of an injured girl, Rachel, draws Nathaniel out of seclusion and into the life of Meredith Butler, his once-fiancée, who takes the girl into her home. Middle brother Finn Boyd’s attraction to the girl turns by degrees more obsessive, his actions toward her more malign.

The conflicts that assail these characters provide this novel its depth. Nathaniel rediscovers his yearning for Meredith, but has he the right to pursue her, given his abandonment of her years earlier? And does Meredith, now ensconced in an passionless marriage, have the right to encourage his interest? Rachel desires to find in Yarmouth Port a sense of home, but can she put shut of past wrongs done to (and by) her? Finn — ambitious, impulsive, overconfident — wishes to command a fleet of schooners but cannot command his father’s affection. Each of these reads real as life, scarred and scoured by the wrongdoing and hardship that attend being human.

Johnson is a master at conveying sense of place, writing of the North Atlantic seaboard with a painter’s eye and a poet’s pen:

Nathaniel rowed toward the jetty, working with a slow motion, letting the boat find its own momentum. The mast of a schooner came into view, then the jetty rocks, slabs of granite stacked like rubble. He rowed alongside them, the slap of the water ringing in his ears, the smell of brine and dried seaweed and broken clamshells with the meat picked clean overwhelming his nostrils. The tide shifted beneath him and swept his boat into the harbor. Familiar sounds struck him, the business of the docks: the creak and strain of a yardarm lifting crates, the clomp of horses pulling wagon carts, and seagulls squawking their comments on the entire scene as if they were the last and final word, angels speaking divinity.

I was once lucky enough to be in the room when the writer Pam Houston offered her view on the possibility of a literary happy ending. Such were possible, she argued, if that happiness were afloat in a sea of sadness. (Note: these are my awkward words — I’m sure whatever Houston said was far better put!) Sara Anne Johnson, it seems to me, has refined Houston’s formula. Happiness, she suggests, is achievable but will be a boon enjoyed by damaged selves, marked as we are by the world’s harshness and the frailties of the people we’ve been.

Crummey’s The Innocents, in which nature in the form of puberty upends the lives of a stranded brother and sister, served warning as we stepped into this unlucky year. We are inevitably the world’s playthings. The Last Sailor assures that we might make some contingent peace with harm as we stumble into the coming year.

Buy Sarah Anne Johnson’s magnificent new work at your local bookseller’s (preferred) or at bookshop.org, an online retailer that devotes part of its profits to supporting independent bookstores.

Note: I recently experienced a sharp example of the hazard inherent in reviewing books by people you know. I agreed to review the second published book by a family friend, an individual close to my writer spouse. Suffice it to say I disliked it, finding it nicely written but poorly researched, dishonest, and naive. Indeed, I disliked it to the point that I did some of the research the writer herself ought to have done, in order to gauge the degree to which she’d fallen short. My review was blistering. But you won’t find it on this site — when time came to click the “post” button, I could not bring myself to undermine my spouse’s friendship. For this reason, going forward, I’ll do many fewer of these. In truth, it’s my role to warn readers away from bad books as much as it is to direct them toward good ones. In allowing relationships to prevent me from posting certain reviews, I’m doing only half of my job.

A Discerning Eye, Carol Orange

First-time novelist Carol Orange offers a take on the historic art heist at Boston’s Gardner Museum.

The robbery, committed by thieves impersonating police officers in the pre-dawn hours of March 18, 1990, resulted in the loss of thirteen objets d’art, each acquired by Museum founder Isabella Gardner. Of these, eleven were paintings of near-stratospheric value, including works by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Degas, Manet, and Flink. None have been recovered. Orange approaches this event with a Tarantino-esque willingness to put a wrench to history to achieve an alternate denouement. Boston art dealer Portia Malatesta feels a piquant tie to the stolen Vermeer (The Concert, https://tinyurl.com/yawv5yqf), through which she feels connected to her deceased brother. Frustrated by the official investigation, Malatesta applies her gallery-owner’s eye to the missing works, searching for commonalities that might provide clues to the “mastermind’s” inner world. To this end, she uses her connections with Boston’s Italian-American community to investigate possible involvement by the Boston Mob, endangering both herself and her marriage. A chance meeting (and an unexpected attraction) brings her to the attention of the FBI, who recruit her to investigate a more promising lead in Medellin, Columbia. In Medellin, she befriends Maria and Carlos Alfonso, daughter and son-in-law of the cartel kingpin. The couple, FBI sources reveal, have installed a secret gallery in their palatial home. The investigation proceeds, mildly close calls transpire, a raid is staged, but is the missing art there to be recovered?

Orange is at her best when she focusses on art, a subject she knows well. The writing in A Discerning Eye is sufficient but short of literary. Dialogue would benefit from shortening and sharpening. 1990s Medellin is a dangerous place, but amateur sleuth Malatesta seems in more danger from marital troubles and rogue attractions than from knives and bullets.

Sleep Well, My Lady, Kwei Quartey

I’m a fan of Kwei Quartey’s. In proof, check my review of his Wife of the Gods (June 4, 2020, https://www.pauleberly.com/criticism/wife-of-the-gods-kwei-quartey). Quartey, like many who plumb the fictional crime universe — particularly the fictional detective universe — peoples his plots with serial protagonists. In the case of his latest, Sleep Well, My Lady, that serial sleuth is Emma Djan, junior detective at Ghana’s Sowa Private Detective Agency. In Sleep Well, Emma and her compatriots investigate the murder of Lady Araba, doyenne of Ghana’s fashion scene.

In some respects, Sleep Well, My Lady strikes one as a throwback or, perhaps, homage to the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, that being the era of Sayers, Christie, Marsh, and their predecessors and contemporaries. Sleep Well is at heart a locked room mystery, the locked room being a staple of early Twentieth Century detective fiction (see note).

The detectives of the Sowa Agency rely heavily on work undercover, impersonating as the plot unspools, reporters, construction laborers, journalism students, and — in Emma’s case — an out-of-work cleaning woman. Almost by definition, the characters who populate crime novels are suspects in whatever outrage animates their various plots and so, I suppose, are reasonably subject to the subterfuge that undercover work requires. Still, I admit I found myself discomforted on a moral basis by Sleep Well’s surplus of this — in some cases, the targets of the Sowa Agency’s misrepresentation are well-meaning citizens, innocent of any wrong-doing.

The first of the Emma Djan novels, The Missing American, focused on computer fraud and its purported connection to traditional Ghanaian shamanism. Its action plays out across multiple continents and involves official corruption at the highest level. Emma and Gordon Tilson, the novel’s victim, are characterized deeply, and indeed each of its large cast of important characters is sensitively drawn. The Missing American is a rewarding piece of fiction and I recommend it.

Thin characterization, however, is a historic weakness of detective stories, likely owing to their original incarnation as literary puzzles. This lack is often compensated by satisfying characterization of the detective him- or herself. There is one mind, the detective’s, that is vividly portrayed, into which the reader can vest her concern, onto which she can project her caring, her need for resolution.

In the case of Sleep Well, My Lady, detectival efforts are allocated not to Emma in particular but are spread among the Sowa Agency’s team. The novel’s most effective characterization is reserved for Lady Araba, its victim. This is a defensible choice — we readers must necessarily care for the murdered to desire her killer be brought to justice.

One misses, however, that central, analyzing eye. In short, one misses Emma. Surrendering her controlling point of view, so integral to The Missing American, reducing it to one among multiple others, saps this latest novel of some of its interest. Literary conventions are good things to violate. But if one is to violate them, one must gain something in trade. More, compared to its predecessor, Sleep Well, My Lady feels like a constricted stage.

Sleep Well does have its merits. Quartey continues to use his fiction to highlight endemic ill-treatment of women, particularly in Ghana, a traditional society in transition. This is a subject to which he brings a Nicholas Kristof level of passion and concern. For him, the detective novel serves as a prism through which he can parse society’s ills. If the locked room mystery is a thing of old, use of the detective tale to comment on social issues is altogether a thing of the present.

I hope to see the courageous, stubborn, and resourceful Emma Djan in other Quartey novels to come, hopefully ones in which she resumes a defining role.

Buy the Emma Djan books at your local bookstore or bookshop.org, an online retailer that donates part of its profit to independent booksellers. Particularly at this moment when so many small businesses struggle, we need to support those folks who make love of the written word their business.

Note: The “locked room” mystery, as exemplified by Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, is one in which the murder occurs or seems to occur in, well, a locked room without any obvious method of ingress or egress on the part of the perpetrator. The device was most popular in the first half of the Twentieth Century and its primary literary practitioner was John Dickson Carr (1906 to 1977). See Julian Symons, Bloody Murder: From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel.

High Treason at the Grand Hotel, Kelly Oliver

When I first participated in writing workshops years back at a state university in the Southwest, I bought into what seemed that program’s regnant narrative. This, I should say, to my discredit. For that narrative was a stern one—literature was serious business, an act of psychological spelunking intended to probe whatever, often mundane situation to uncover whatever shattering (discomforting... disturbing... transgressive... transformative... pick your own overwrought adjective) kernel of truth might lurk within.

I became a believer! By the Lit-Fic Borg, I’d been assimilated! The crime and espionage fiction on which I’d subsisted through college became an embarrassing memory. Science fiction and fantasy, mainstays of my high-school years, did not deserve mention. I went overboard. I remember sitting in one writing prof’s office and informing her that I’d come to believe that literature oughtn’t be about much of anything—its terrain ought to be the dreary quotidian, its task to rip away the scab of the ordinary and reveal the unhealed flesh beneath.

Stephen King—or, rather, the fact of him—delivered the first hammer blow to this wall I’d erected between myself and much of the world of letters. As I sat one day in workshop, listening to another fledgling writer outgas regarding King’s shortcomings (a bit of a lit-student go-to, that; I’d probably done it myself) a particular thought occurred to me—yeah, said thought went, SK’s no Thomas Mann, but he entertains hundreds of millions of readers. You can go your whole life and not meet another person who’s read The Magic Mountain. Try that with Carrie, or Salem’s Lot, or The Shining.

And is entertaining bazillions of readers not worth something? Or is it that reflexive rejection of popular, less literary fiction is fatally problematic? In either event, my self-erected wall commenced to crumble. My recovery from literary snootiness had begun...

...making me, ultimately, into the reader I am today—one who can snatch up a novel intended for simple entertainment, like Kelly Oliver’s High Treason at the Grand Hotel, and be, well, entertained by it.

Fiona Figg, file clerk in Room 40, World War One Britain’s nearly all-male center for code-breaking, finds herself by dint of her photographic memory in wartime Paris, shadowing the elusive Frederick Fredericks—journalist, big-game hunter, and (Fiona suspects) assassin specializing in the, erh...removal of double agents.

As she seeks proof of Frederick’s treachery, Fiona contends with her button-down superiors in British Intelligence; with the exotic dancer, Mata Hari; with the Paris Gendarmes and Louis Renault, founder of the French auto empire. Toss in, for good measure the odd serial killer; the charming Aussie, Archie Somersby; and, most obtrusively, the gallant and seemingly dull-witted British officer, Clifford Douglas, Fiona’s suitor and—inconveniently—Frederick’s fast friend.